Trust Me

merging psychological safety and five dysfunctions

Psychological safety is one of those terms that gets thrown around far more often than it’s actually practiced. It’s great to talk about, but meaningless if leaders don’t work vigilantly to make it a reality.

How It Starts

Peter runs an organization that he insists has psychological safety. He knows it, because he tells the org constantly that they are safe to raise any idea or challenge anything without repercussion. Peter also dismisses any idea that isn’t his, and bullies people who disagree with him. Peter doesn’t walk the talk.

I’ve worked for Peter before. He went to the management and leadership classes where they talked about building trust and not being afraid to fail. Unfortunately, in more stressful times, Peter berated people for making mistakes, and focused far more on blame and covering his own ass than he did building a learning organization.

Two Models

On a (fairly?) recent episode of Pat Lencioni’s At The Table podcast, he discussed Psychological Safety. It was interesting to me, as both a fan of all of Lencioni’s books, as well as everything Amy Edmondson has ever written (but especially The Fearless Organization, where Edmondson discusses team psychological safety).

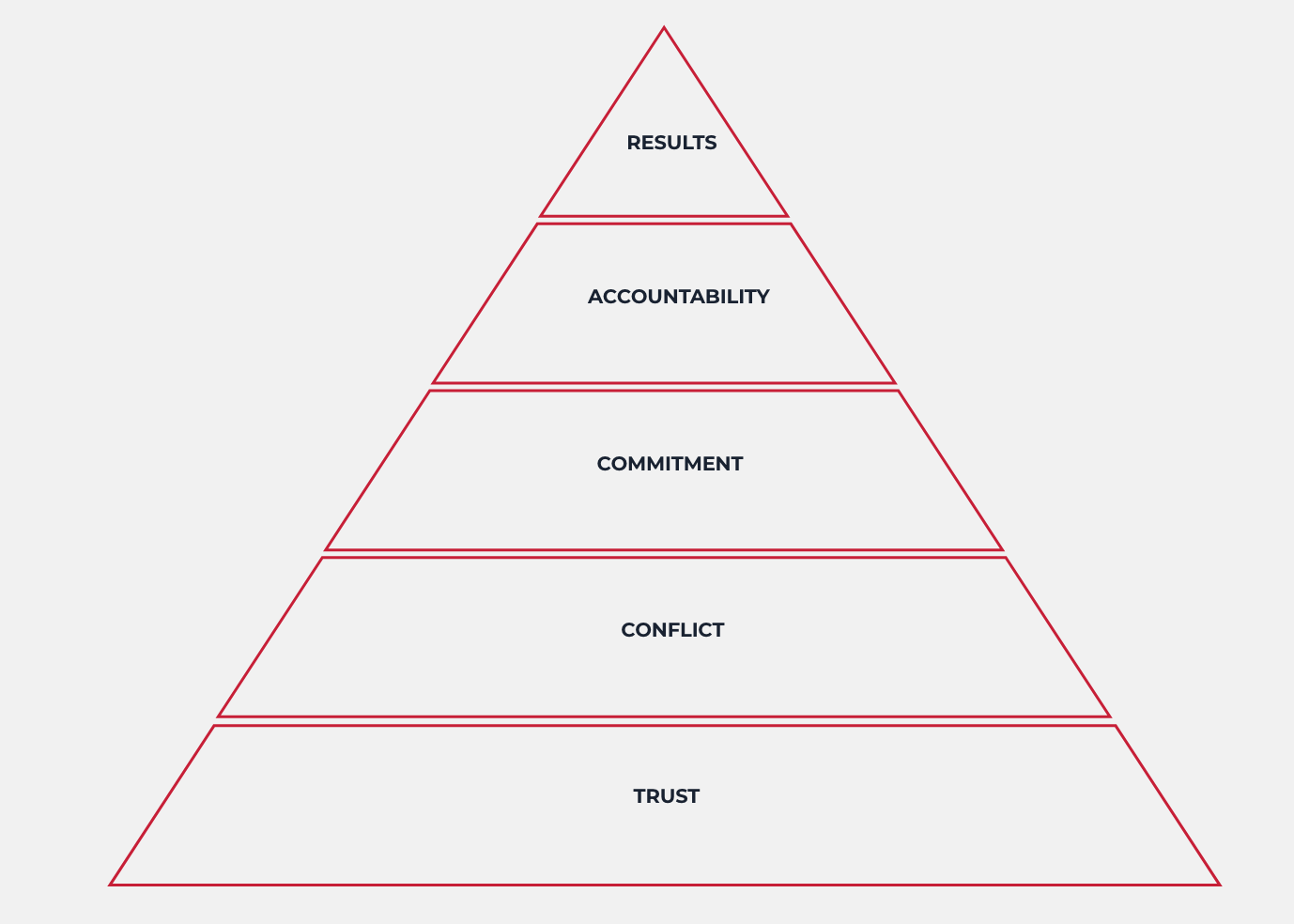

It was surprising to me to discover that Lencioni and his team weren’t familiar with the psychological safety term and were wary of it…until they discovered it was quite similar to the trust model that he wrote about in The Five Dysfunctions of a Team.

There are some strong parallels between Edmondson and Lencioni’s work - especially when looking at her Team Climate Inventory worksheets.

It Starts With Trust

In both Lencioni's model and psychological safety, trust is foundational. Lencioni emphasizes vulnerability-based trust, where team members feel safe admitting weaknesses or mistakes. In psychological safety, trust manifests as feeling safe to take risks without fear of embarrassment or retaliation.

Fear of Conflict vs. Encouraging Constructive Debate:

Psychological safety supports open, constructive conflict. In Lencioni's model, the fear of conflict impedes team progress. A psychologically safe environment fosters healthy debates, which is essential for teams to address issues openly.

Lack of Commitment vs. Shared Ownership:

In psychological safety, team members contribute openly to decisions and feel ownership, driving commitment. In Lencioni's model, lack of commitment happens when there’s ambiguity, often caused by avoiding conflict. Psychological safety helps overcome this by allowing diverse viewpoints to be considered, increasing buy-in.

Avoidance of Accountability vs. Support for Mistakes:

Psychological safety encourages accountability because people feel safe to hold each other responsible in a constructive way. In Lencioni's dysfunction, teams avoid accountability because trust isn't strong enough. With psychological safety, mistakes can be learning experiences, and accountability becomes less personal and more growth-oriented.

Inattention to Results vs. Shared Goals:

Both models emphasize the importance of focusing on collective results. Psychological safety encourages teams to focus on shared goals rather than individual performance. In Lencioni's model, a lack of attention to results stems from dysfunctions lower in the pyramid.

Most importantly, both models share an emphasis on vulnerability and openness. Teams need to feel safe to admit mistakes and share divergent opinions

Early in the podcast, Lencioni says that “it is critical to create psychological safety in your organization…but that doesn’t mean that it’s going to be uncomfortable or involve some risk.” In my experience, it’s this risk that causes a failure to walk the talk with organizational safety.

I’ve been thinking about how Lencioni and Edmondson’s models complement each other for months, but finally feel like I know enough to write it down - and talk about how to use both models to improve organizations.

The Hard(er) Part

It’s easy to read about this stuff, and it’s only slightly more difficult to write about it. The hard part is putting it into practice. It take consistent effort over a long period of time to build psychological safety or to defeat the five dysfunctions. But - like most hard problems, the hardest part is starting.

Trust

Start by building trust across the team. Create opportunities (both synchronous and async) where leaders and team members can share personal stories, admit mistakes, and offer help to each other. It starts with leaders being vulnerable. Peter insisted on being right about everything, and that halted a lot of conversations. Instead, work on creating norms around openness and active listening.

Conflict

Too many leaders actively avoid conflict and fail to recognize that conflict is an opportunity for growth. Teams should see disagreements not as personal attacks but as discussions aimed at improving ideas or solving problems. Leaders should facilitate structure debates where diverse viewpoints are actively encouraged and rewarded. Everyone on the team from the newest newhire to the most senior leader should feel comfortable challenging ideas. This helps prevent groupthink and fuels innovation.

Clarity and Commitment

After encouraging open debate, ensure that every team member has a clear understanding of decisions and feels committed to them. A lot of the ideas from my post on Decision Making - including disagree and commit apply well to this growth step.

The main thing to remember here is that if people felt like their voice has been heard in a discussion or debate, they are much more likely to support and move forward with the decision. As leaders, we need to avoid passive buy-in and encourage genuine and wide commitment.

Accountability

Once team members trust each other and are aligned on decisions, they should hold each other accountable for delivering work aligned toward the team goal. Frequent feedback loops among the team members that addresses concerns and builds for the future is important. This feedback should be given in a way that focuses on the behavior, not the person. Encourage "feedforward" (suggestions for future improvement) instead of only dwelling on past mistakes. Team members should be comfortable giving each other feedback - and in doing so, will create a culture of accountability.

Results

From the leadership angle, keep the focus on team and organizational goals rather than individual performance. In psychologically safe environments, team members are more likely to collaborate and work toward shared success rather than hoard information in a silo.

Take time in team meetings to review team goals and individual contributions. Use transparent metrics that reflect collective performance and celebrate wins as a team. This will actively combat inattention to results, as teams become more results-driven and collaborative.

Walking the Talk

I’m liking the combined models of five dysfunctions and team climate inventory. In the end, it really comes down to a few specific things that leaders should do if they don’t want to act like Peter.

First, leaders should model the behaviors expected from teams, such as vulnerability, conflict resolution, and accountability. They should provide training to managers and team leads on how to foster psychological safety through active listening, feedback techniques, and conflict management. They should establish cultural norms that encourage behaviors like respectful dissent, inclusion in decision-making, and continuous learning from failures, and above all, they should collect feedback to ensure that they are truly walking the talk.